The professionalization of English medium instruction lecturer: content and certification

- Law Institute, Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia

As there is no unified standard for EMI teacher professional certification, this paper surveys the professional competence requirements and professional certification of English medium instruction (EMI) lecturers worldwide in order to inform decisions by researchers and administrators tasked with the design and delivery of the certification activity. The study uses a semi-systematic review method to tease 46 articles which include information about EMI lecturer ability, professional development, and certification. The paper analyzed the content of them about competence components and delivery methods. The analysis reveals five main dimensions: language competence, communicate competence, pedagogical competence, multicultural competence and EMI awareness. The certification in current can be divided into two categories depending on whether they include a training program. Certification that consists only of tests usually focuses more on the teacher’s English proficiency in teaching. Another certification usually has the essential English requirement for the participants and pays more attention to the pedagogical methodology. The paper concludes with recommendations for the development of the EMI lecturer competence framework and certification program.

Introduction

Higher education institutions are promoting EMI teaching to increase their schools’ internationalization, enhance their prestige, and attract quality students from abroad. In this context, the key factor influencing teaching and learning—teachers—is beginning to receive attention. Studies have found that achieving professionalization of EMI teachers not only facilitates efficient and high-quality teaching but also further promotes the internationalization process of universities and contributes to their higher international status (Ulla et al., 2022). Agarao-Fernandez argues that an important indicator of teacher professionalization is the extent to which school teachers have received formal training from an accredited program and are tested and certified in areas such as teaching skills and subject knowledge, especially in the areas they will be assigned to teach. The same applies to the professionalization of EMI teachers. Identifying the required competencies and certifying EMI teachers is an initiative that can promote the professionalization of the EMI teacher community and effectively ensure the interests of all parties involved in EMI teaching (Agarao-Fernandez and Guzman, 2006).

However, the current facts should be more impressive. A survey of EMI instructor qualifications conducted by Dearden found that when asked, “Do you think there are enough qualified EMI instructors in your country to teach EMI? “83.6 percent of the 55 countries surveyed answered “no” (Dearden, 2014). The Macaro study found that only 23.4% of teachers were aware of the existence of EMI teacher certification. Nearly half of the educational institutions do not offer certification, and they do not require their teachers to obtain this specific certification (Macaro et al., 2020). The lack of official certification has resulted in the threshold for becoming an EMI teacher becoming arbitrary. Some EMI teachers in schools are assigned or approved by department heads or older teachers, while others volunteer to become EMI teachers based on personal interest or practical needs (e.g., the presence of international students in their classes; Macaro et al., 2019; Macaro and Han, 2020). Developing a standardized requirement to screen EMI teachers is a current issue that needs to be addressed, as well as the hope of most EMI teachers (Macaro and Han, 2020).

This paper conducted a search using EMI, teacher professional development, and certification as keywords, and the articles obtained were then stripped of those that were not strongly related to the topic or whose research was conducted on teachers at non-higher education levels, resulting in 38 articles, which were organized and analyzed to explore the following questions.

1. What should be included in the professionalization of EMI teachers?

2. What are the existing forms of professional certification for EMI teachers?

Research methodology

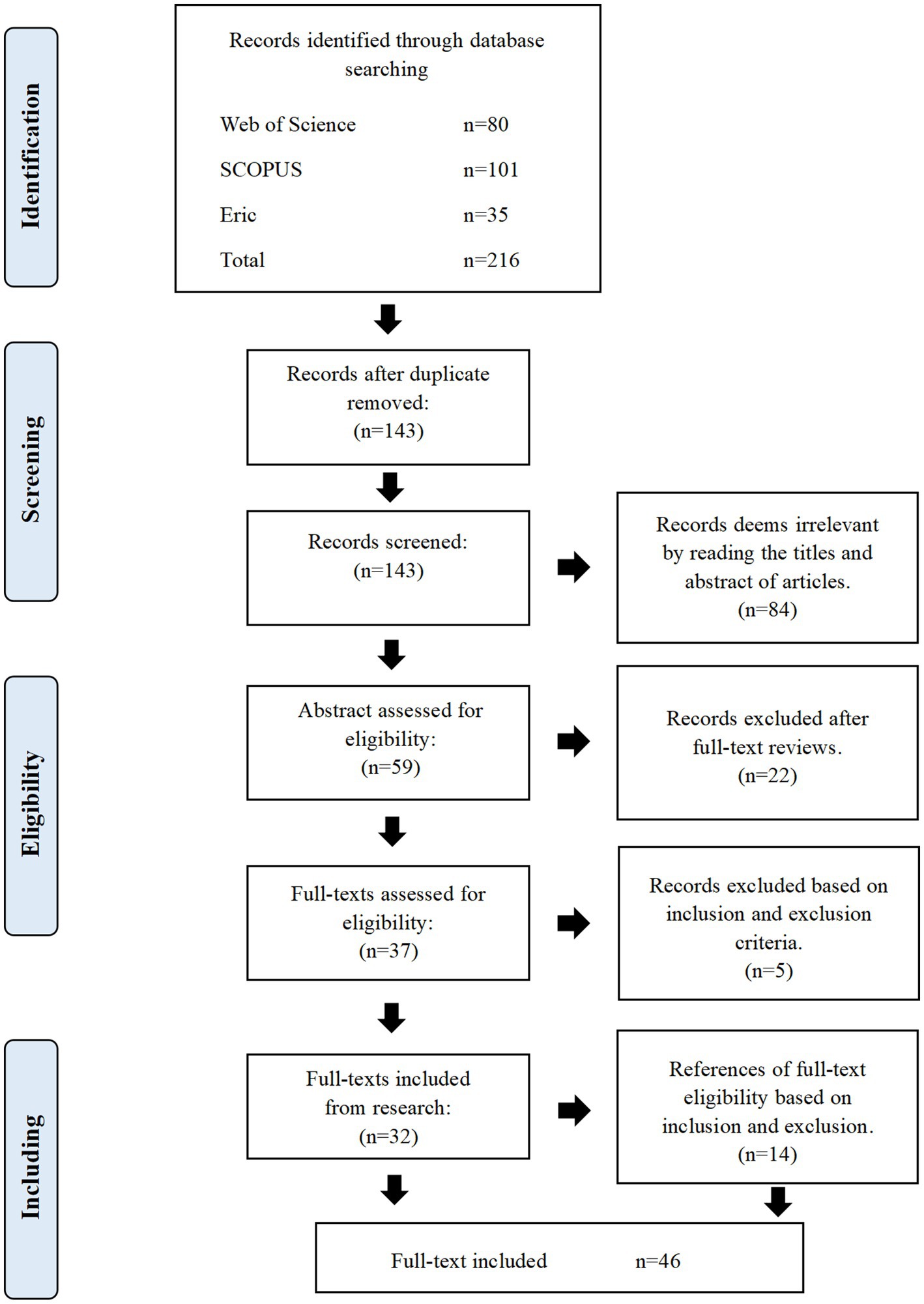

Semi-systematic reviews are usually used when combing studies on a topic, they are scattered in different disciplines, research groups, and such a status of research may hinder the process of complete systematic review of the topic. Therefore, different strategies need to be developed to achieve the purpose of combing and reviewing (Snyder, 2019). The search revealed that the current number of relevant specialized studies is still low, and many explorations of EMI teachers’ professional competencies as well as reviews are included in studies on topics such as EMI training, etc. Therefore, this approach was considered appropriate to meet the purpose of the current study and to answer the research question.

Search strategy

In order to locate relevant studies for the review, a search for articles was conducted in major electronic databases in Web of Science, Scopus and Eric. As EMI teacher research emerged relatively late compared to teacher research in other disciplines, and a large number of articles have appeared only in the last decade. Therefore, no time limit was set in the search for this study, and it was also intended to sort out the development of the research. The search terms, including combinations and derivatives used in the electronic database search, were: (English Medium Instruction OR EMI), (teacher* OR faculty*), (competence*), (certification*OR assess*), (criterion* OR standard*). These terms were combined using the Boolean operator “AND.” In order to include as many eligible articles as possible, this study will also check the citations of the selected literatures. Relevant literature is also included in the study. See Figure 1 for a summary of each stage of the search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria used to identify relevant articles for the review included: (a)written in English, (b) the study subjects belonged into tertiary level, (c) studies included the information about certification program or EMI teacher’s professional language competence, communicative competence, teaching competence or other relative competence. (d) The citations obtained after the screening of the above conditions will also be included if they meet the above three conditions.

The exclusion criteria applied to eliminate searched articles from the review were as follows: (a) articles not written in English, (b) duplicated articles across database, (c) EMI teacher in primary school and middle school, (d) articles focused only on explaining teaching strategies or discuss advantage and disadvantage of them, (e) articles mentioned some certain competence but there is no evidence it relevant to professional competence, (f) articles gave detailed information about some training program which certification or assessment in not included, and (g) reviews, editorial commentaries and opinion pieces.

Data analysis process and demographic result

The thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was applied in the current analysis. Data were analyzed from each selected article’s results/findings and discussion sections if an article included disaggregated data. All articles were read at least three times, as the initial reading aimed to understand the contents of the articles, subsequent reading was used to code articles inductively, and final reading was conducted to review and revise the codes in order to increase the veracity of the data analysis.

The research comprises 46 articles. They were published from 2010 to 2023. Most of the them focus on the period between 2019 and 2022. The studies came from 18 countries around the world: Spain, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the UK, Croatia, Italy, Germany, China, Japan, Korea, Brazil, Mexico, Turkey, Australia, and New Zealand. Most of them from Europe.

On the whole, the relevant paper description was rather limited. The most detailed descriptions of the lecturer certification program can be found in several papers. Few papers discussed the professional competency criteria specifically. Relevant content is mostly found in papers that examine the effectiveness of teacher training programs, teacher attitudes toward professional development, and teacher needs and difficulties. They did not specifically discuss the requirements of professional ability but reflected the requirements of EMI teachers’ ability from the perspective of professionals, managers, or teachers. The usefulness of the current survey lies in bringing together this scattered information so that the administration department, EMI program leaders, and lecturers have overviews to help them with the scientific design, effective implementation of the certification, and targeted development the professional skills.

It will nevertheless be appreciated that s significant limitation of this data collection approach is that many EMI certification programs are not published. Due to the lack of relevant literature, the data of the survey is not enough to cover most parts of the world, and most studies are still concentrated in Europe and America. Therefore, the degree of matching between the research conclusion and the actual situation in other regions still needs to be further investigated and determined.

Research findings

Content of professionalization

“Competence” can be defined as the expertise, understanding, and skills needed to effectively teach academic subjects through the medium of English (Macaro et al., 2020). Of the total literature combed, only four articles provided a more complete framework of professional development competencies for EMI teachers (Dang and Vu, 2020; Macaro and Han, 2020; Rubio-Alcalá and Mallorquín, 2020; Richards and Pun, 2022). More studies focused on one aspect of professional competencies. In this section, different competencies will be used as clues for detailed combing.

Language competence

EMI teachers’ language proficiency is defined by some scholars as having the appropriate skills to use the wide range of language resources that may be needed in classroom practice (Rubio-Alcalá and Mallorquín, 2020). Existing studies show that EMI teachers, students and researchers all include language ability in EMI professional competence (Helm and Guarda, 2015; Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović, 2018; Cañado, 2020; Gustafsson, 2020). In Helm and Guarda’s research, the vast majority of teachers surveyed believe that English language proficiency is a required professional competency and that they need to improve it (Helm and Guarda, 2015). Hendriks and van Meurs (2022) collected perceptions of EMI instructors’ professional competence from students’ perspectives and found that they cared more about instructors’ language skills and that some students might complain about instructors’ English pronunciation. Most certification programs specifically designed by academics include language proficiency as a foundational items, such as TOEPAS and PLATE (Dimova, 2017; Gundermann and Dubow, 2018). Some programs will focus more fully and carefully on teachers’ speaking and writing skills (Kling and Hjulmand, 2008). The program at the University of Freiburg focuses on English proficiency into Fluency, Articulation and pronunciation, Grammatical accuracy, Lexical range and accuracy, and Code consistency (Gundermann and Dubow, 2018).

The content of language skills is constantly being enriched. Macaro and Han (2020) found the content of English competence should include not only teachers’ general English but also language proficiency based on teachers’ respective subject areas. Tsui (2017) argued that teachers should master English for English-teaching professionals, accents and dialects, and world Englishers. Gustafsson (2020) suggests that language competence in EMI teaching can be specific to the teacher’s use of grammar and vocabulary. Because highly specific language structures and functions occur in specific contexts, language formulas can be summarized through research to form a language bank (Gustafsson, 2020).

Communicate competence

Communicative competence refers to an instructor’s ability to teach in English and successfully convey information (Crespo and Tojeiro, 2018). Communicative competence can also be thought of as a pragmatic competence, the ability to use language effectively in a contextually appropriate manner to suit the environment and the intended audience or reader (Carrió-Pastor, 2020). An interesting finding is that Studer (2015), through a survey of students, identified positive classroom experiences that usually demonstrated the teacher’s communicative competence, although the language skills of the teacher in this matter may have been any weaker. Certainly, communication competence does not stop at this single connotation. Dang and Vu (2020) argues that in classroom situations, communication between teachers and students occurs in the form of questions and answers from the teacher. This form of communication aims to develop learners’ ability to question, check, and relate, and to explain. This ability also includes the teacher’s ability to build rapport with students through the medium of instruction and the use of inclusive language (Dang and Vu, 2020). Crespo and Tojeiro (2018) also suggest that it also includes a sociocultural dimension, which requires so-called strategic competence, or “compensatory strategies” in situations of grammatical or sociolinguistic or discourse difficulties, whereby both verbal and nonverbal communication should be taken into account (Crespo and Tojeiro, 2018). Multimodal communicative competence is beginning to be looked at in the context of such a concept. It is defined as being about the ability to make various modalities work together to produce comprehensible meaning (Costa and Mair, 2022). The study of Morell et al. (2022a) found that the coordination of multiple modalities in addition to language can provide additional support for students to comprehend not only the content but also the language of instruction. Instructors who coordinated spoken and written language, graphic elements, gestures, and body language were more successful in constructing their concepts and making the classroom more cohesive (Morell et al., 2022b). Communication skills have also been noted by some existing certification programs. For example, communicative competence is examined in terms of articulation, rhyme, initiation and integration of student input, and response to student input in a program designed by University of Freiburg (Gundermann and Dubow, 2018).

Pedagogical competence

Pedagogical competency is defined as the ability of teachers to have the ability to organize and plan learning tasks that help students learn knowledge with high quality and efficiency (Rubio-Alcalá and Mallorquín, 2020). It is the professional competence of teachers is useless to question, but there is some controversy about whether to include a professional knowledge and teaching skills component in the assessment of EMI teachers. In the study of Dimova and Kling (2018), it was noted that all EMI lecturers in Europe are employed by universities for their subject matter expertise, and many of them have extensive teaching experience in local languages. Therefore, the assessment of subject matter knowledge and teaching skills becomes redundant (Dimova and Kling, 2018). However, many scholars arguing that it is not ideal (Dafouz et al., 2007; Cots, 2013; Dearden, 2014; O’Dowd, 2018). Many studies have repeatedly shown that teaching subjects in English are much more than simply translating classroom content into a second language, and teachers should not be expected to intuitively figure out techniques for teaching through English (Dafouz et al., 2007; Cots, 2013). And some surveys also show that EMI teachers continue to have a need to improve their teaching competence (Piquer-Píriz and Castellano-Risco, 2021; Uehara and Kojima, 2021).

Richards and Pun (2022) argue that EMI teachers should have the ability to develop strategies to adapt EMI instruction to support the learning of students with different levels of English proficiency. Tsui proposed the development of teaching skills including but not limited to English presentation skills, lesson planning and delivery, classroom management, task-based learning, cooperative learning, case teaching, handling large and small classes, flipped classrooms, and assessment (Tsui, 2017). Rubio-Alcalá and Mallorquín sorted out the teaching competencies of EMI teachers according to the teaching process. They define pedagogical competency as the ability of teachers to have the ability to organize and plan learning tasks that help students learn knowledge with high quality and efficiency. This competency is essential for teachers to develop their teaching practices appropriately and to provide structure to their students in the teaching and learning process. It should address all elements of the curriculum planning and instructional phases. To this end, the researchers proposed 18 specific indicators of pedagogical competence that encompass the entire process from the beginning of the lesson design until the end of the class when students are evaluated and then a new round of pre-reading tasks is set for them, for example, teachers can set the objectives of the syllabus considering the context and participants and set pre-class readings or videos to prepare students for new learning (Rubio-Alcalá and Mallorquín, 2020). Another group of researchers has suggested a more specific teaching competency requirement—the teacher’s ability to interact in the classroom. In addition, it is worth noting that some studies specifically mention that EMI teaching requires teachers to have a learner-centered teaching attitude (Crespo and Tojeiro, 2018).

Multicultural competence

In parallel to the language and pedagogical skills mentioned above, intercultural communication skills are also considered to be one of the determinants of lecturers’ ability to impart subject knowledge and achieve effective classes (Wang, 2023). Crespo and Tojeiro define intercultural competence as meaning “the integration of new values, the respect for other values and the valorization of otherness that derive from the coexistence of different ethnic groups and cultures that develop in the same or different societies, while promoting the enrichment of the identity of each culture with which it comes into contact. And the specific response of such competencies in teaching is that the teacher is an important mediator in helping students learn the language, the cultural beliefs, values and tenets behind the language, and that in the process of acquiring knowledge, the teacher and students will promote intercultural communication (Crespo and Tojeiro, 2018). Safipour et al.’s (2017) study agrees with this view and further explains this part. Their study found that while language proficiency was a major barrier to the integration of foreign students in an EMI program with local students, differences in academic culture appeared to be a greater barrier (Safipour et al., 2017). Dubow et al. (2021) referred to a similar competency in their study as the intercultural transparency competency. The focus of this competency is the teacher’s ability to link basic concepts such as localized geopolitics as examples to classroom content in an internationalized classroom, which allows for faster adaptation and integration of students new to local learning (Dubow et al., 2021). the international transferable competencies mentioned in Macaro and Han’s framework competencies mentioned in Macaro and Han’s framework are also similar. In their study, they also considered the specific competencies required for EMI teaching to be implemented in different national contexts, so they proposed another dimension of professional competency development in national context competencies (Macaro and Han, 2020).

EMI awareness

Another dimension of professional development that is also often mentioned by researchers is one that is considered from the perspective of EMI teachers themselves-namely, the development of EMI teachers’ professional perceptions. Research shows that teachers’ cognition of EMI teaching directly affects students’ learning effect (Jiang et al., 2019). Fortanet-Gómez mentions that professional development also requires enhancing teachers’ knowledge about EMI, for example, introducing EMI-related policies and rules to help teachers further understand why EMI was introduced, and if this component is to be added to the professional development curriculum, it should be placed at the very beginning of the curriculum (Fortanet-Gómez, 2020). Chen and Peng (2019) introduced a specific module in a professional development program implemented in mainland China to improve teachers’ knowledge about the EMI curriculum as well as their teaching. Specific content includes reflection and discussion on the nature and characteristics of EMI instruction, the role of language in content learning, and how to balance effectiveness and accuracy in EMI classroom communication (Chen and Peng, 2019). Yuan (2020) advocates promoting EMI teachers’ sense of ownership of English. Teachers should recognize that effective English language teaching relies on comprehensible and meaningful communication rather than native-like English (Yuan, 2020).

The criteria of the professionalization

Although researchers have focused on a variety of competencies for the professional development of EMI teachers and the connotations of each are being extended, a problem that cannot be ignored is that, to date, no clear criteria for EMI teacher competencies have emerged and becoming an EMI teacher at some universities is an arbitrary matter. In Maraco’s study, one Chinese faculty mentioned that in their department, it is up to some older professors to decide and approve someone’s ability to teach in English medium (Macaro et al., 2019). Further, taking language proficiency as an example, 43% of teachers in the survey of O’Dowd (2018) required their English proficiency to be B2, but 44% needed C1 level and 13% needed C2. There is no consensus on the standard of English proficiency for EMI teachers (O’Dowd, 2018). Level C1 of the CEFR has been widely accepted as the minimum level of English required for effective instruction in EMI classrooms, although this requirement has not been supported by empirical research (Dimova, 2021).

The connotation of the standard is also changing. In the initial stage, many universities required language proficiency of teachers by directly using the internationally recognized academic English test standard as the first choice for assessing the language proficiency of EMI teachers in universities. The IELTS test or the Common European Frame of Reference (CEFR) standards were the most commonly used standards for English proficiency (Klaassen and Bos, 2010; Martínez and González, 2017). The policy of the Northern University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands specifies that teaching staff who teach in a language other than Dutch will be qualified in the language of instruction, and the university has set the criteria based on the internationally recognized English proficiency test, based on empirical principles (Troia, 2013). Martínez and González (2017) suggest that Spanish universities set the C1 level of the CEFR as a minimum requirement for English for teachers of bilingual or multilingual degree programs. In addition, some regions or some schools have developed their own English tests, whose assessment criteria are also based on the above-mentioned language tests (Klaassen and Bos, 2010; Ball and Lindsay, 2013). The benefits of doing so are obvious. These standardized tests ensure the greatest degree of scientific, comprehensive, and accurate assessment of teachers’ English proficiency. Such assessment criteria are also internationally accepted. However, as the professional development of EMI teachers has been studied, more and more scholars have argued that the standard English-based language tests for native English speakers are not appropriate for EMI teachers who speak English as a second or third language.

Pilkinton-Pihko argued in her study that the assessment tendencies of second-language speakers should be different from those of native speaker norms (Pilkinton-Pihko, 2013). Since EMI teaching in many universities is currently conducted in a multilingual and multicultural context, for most EMI teachers who speak English as a second or third language, the normative reference of native English speakers is implied, and English assessment criteria focusing on more standard pronunciation, and greater vocabulary use do not seem to be sufficient evidence that teachers who achieve better grades can teach perfectly in English (Díaz Pérez et al., 2019). On the other hand, these tests do not prove that the English reading and writing skills that some teachers acquired during their doctoral studies transfer perfectly to effectively explain key concepts to students in a way that makes classroom content easy to understand (Barnard, 2014). Therefore, it is important to investigate the target area of language use when setting language proficiency standards for EMI teachers. The criteria for English should be to identify the specific communicative tasks that teachers engage in real life and analyze the successful language use associated with these tasks in order to stimulate the same types of tasks and the same language functions with the test. The correct evaluation criteria should understand the tasks to be performed by the instructor in the teaching domain, or other domains deemed necessary, e.g., instruction, meetings, etc. The characteristics of language use in the EMI domain should be described in order to serve as a measure of test performance (Dimova, 2020).

The mode of certification

The definition of “certification” is expanded slightly in this study to provide evidence of the competencies needed to teach a particular subject in a particular way, Although Dimova included training programs to support EMI instructors as a means of certification in her study (Dimova, 2020), this study screened the training programs based on the above definition of certification. Only programs that explicitly stated that it included teacher certification as a purpose were selected for inclusion in this study. In addition, the certification through existing tests mentioned in her study, such as the International English Language Standards tests (IELTS, TOEFL, Oxford placement test and DIALANG, etc.) are not specifically designed for EMI teachers, and these tests only examine teachers’ These tests are not designed specifically for EMI teachers, and they only measure teachers’ general English proficiency, and are therefore outside the scope of this paper.

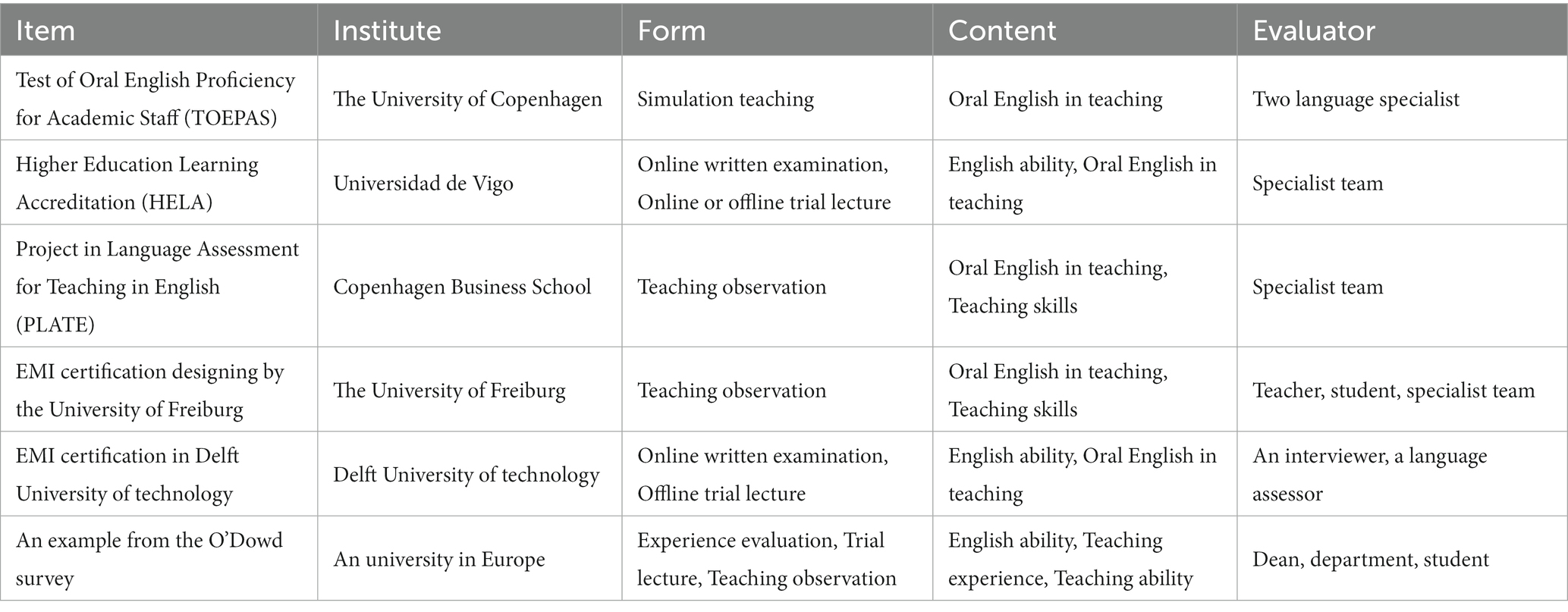

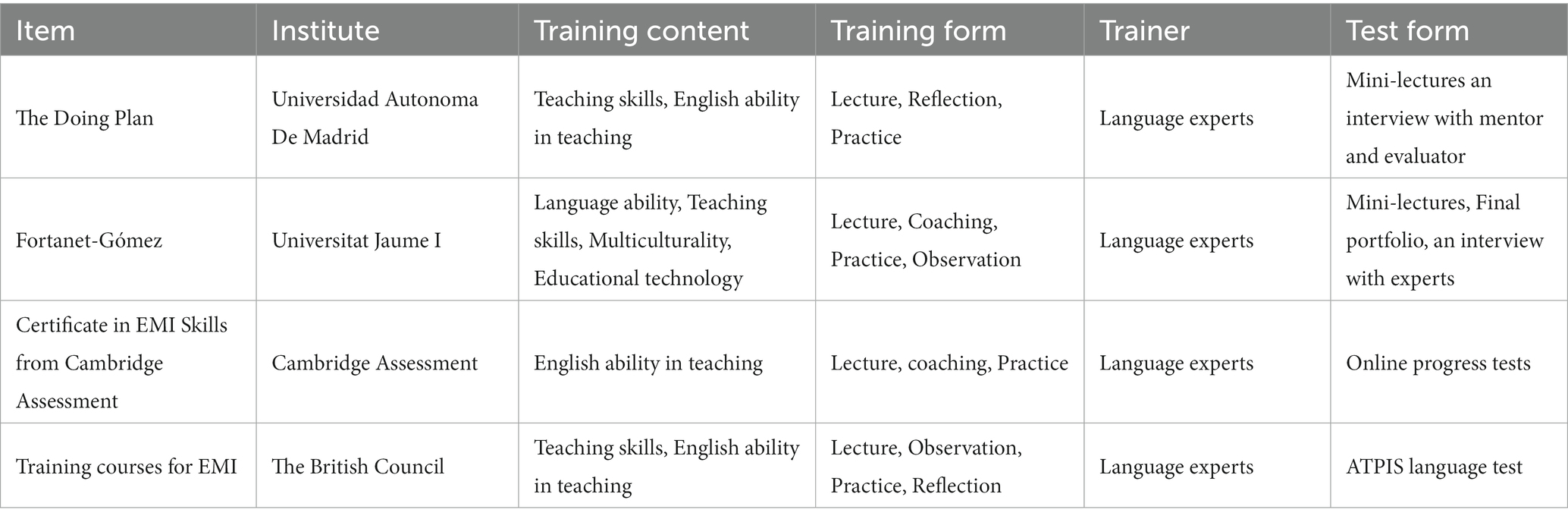

Thus, this section divides certification programs into exam-only and training with exam, depending on whether the program has a training component. A total of 10 assessment certification programs of these two types are summarized refer to Tables 1, 2. The first mode of the certification programs is exam-only mode. This type of certification requires teachers to prepare for their own exams. Since most programs are designed specifically for college teachers, the tests are usually set up on campus in a face-to-face format. Of course, given the practicalities, some certification programs can also be administered through an online format. The second mode is a training program with an exam. This type of certification is usually for in-service teachers. They may range in duration from a few months to several years. Their focus is more on the training part.

The format of certification

Format

The most basic format of an accreditation program is an exam. The Higher Education Learning Accreditation (HELA) program is a representative example of this type of exam. The written portion of the test requires candidates to write a short essay of 200–300 words in English on the spot within a set time frame. The oral test then requires a 7-min presentation, after which the examiner will ask the candidate impromptu questions that will be included in the scoring (Diaz-Caneiro, 2017; Universidade de Vigo, 2023). Similarly, Delft University of Technology has a competency-based program designed specifically for EMI teachers. The written portion of the test is a 30-min online test. The oral test is also 30 min in total and consists of four sessions: give an introductory talk, give a 5-min presentation, describe and explain on the basis of a picture a trend in their disciplinary field and interact with the interviewer and conduct a role-play between a student and a lecturer (Klaassen and Bos, 2010). The two programs are very comparable, and the examiner question and answer session at the end of the speaking test have similarities to the teacher-student role-play session intended to simulate a classroom. However, due to the time constraints of the exam, such a session is conducted for a very short period of time, so it is difficult to reflect the teacher’s true level of performance in the classroom in a short period of time. The Test of Oral English Proficiency for Academic Staff (TOEPAS) program below seems to avoid this problem. It simulates teaching in a controlled environment and scores the candidate’s live performance. Each test lasts approximately 2 h and involves the assessment of three instructors in the same course or area of specialization. Test takers take turns delivering prepared mini-presentations and participating in role plays as “students” to simulate a graduate classroom environment. As “students,” participants were asked to interrupt the lecturers (testers) during the lecture and to ask spontaneous questions at the end of the lecture (Dimova, 2017). Such a format seems practical, as three test takers from the same discipline or profession enable them to interact meaningfully on specialized topics and better mimic the actual teaching environment. However, some scholars argue that in a testing environment, it is possible to assess EMI teachers’ performance in a particular skill but ignore communicative competence in real teaching environments (Gundermann and Dubow, 2018). Based on this, some programs choose to evaluate directly in the actual classroom. The Project in Language Assessment for Teaching in English (PLATE) program communicates with the teacher being assessed in advance to determine a particular time and place for the teacher to teach. The evaluation team attends the teacher’s classroom and evaluates the teacher’s performance through observation (Kling and Hjulmand, 2008). The EMI teacher certification implemented at the University of Freiburg also uses classroom observation (Gundermann and Dubow, 2018). In addition to this, O’Dowd (2018) introduces a more comprehensive approach through a survey. Teachers will be examined for their English language certificates, past performance in English, and overseas experience. They will then go through an interview and also be asked to lecture in English and have their performance evaluated (O’Dowd, 2018).

Certification programs with training are much richer, both in the form of training and in the form of certification exams that need to be taken afterward. Lectures and lectures, the basic form of training, are covered in almost all programs of this type. In addition, practice is an essential part of the program, and both the program designed by Fortanet-Gómez (2020) and the certification program offered by the British Council mention the need for teachers to teach in microgrids during the program. The Cambridge Assessment requires participants to conduct small group practice sessions. The Doing Plan requires teachers to conduct teaching time activities ranging from 20 to 60 h at the end of the program. Coaching and Reflection also seem to be more mainstream training approaches. Assigning special tutors to trainees is present in most of the programs. Reflection activities are often linked to other activities; The Doing Plan links mentoring to reflection, and the English Cultural Institute links reflection to practice. Other programs include observation activities, including observing other teachers’ EMI sessions on campus and conducting listening trips abroad (British Council, 2014; Fonseca et al., 2020; Fortanet-Gómez, 2020; Universidad Autónoma De Madrid, 2020; Cambridge University Press and Assessment, 2023). It is important to note that most of the courses are conducted in a modular format, which means that teachers can arrange the sequence, timing and others according to their own circumstances. The final assessment of these programs is not in the form of a summative exam but rather in the form of a process evaluation. Teachers are required to complete the requirements of each session as they participate in the program, with some requiring a final portfolio and others requiring teachers to demonstrate the results of their training in practice.

Evaluator and trainer

The evaluators and trainers who appear in certification programs are fundamentally different from those being evaluated in terms of their specialization and first language. Since accreditation has an authoritative requirement, when the training and certification is about language proficiency, the person in charge of this component is usually a language expert, some from the same country as the program, with a first language that is also non-English. Some schools also hire foreign linguists whose first language is English to conduct the evaluation. For example, Cambridge Assessment and the British Council offer certification programs with trainers from the UK. Of course, this is because these types of organizations themselves provide all kinds of language training, not just for EMI teachers, so they are more resourceful. It may be difficult for some moderately developed universities to select senior language experts from within the university or to hire outside experts. And there are also studies that show that teachers prefer that evaluators come from outside the college or even the school rather than being observed by a supervisor or superior. This is because observers from unified colleges may have potential conflicts of interest, and it is difficult to ensure the objectivity of supervisors or bosses when evaluating (Airey, 2015; Macaro et al., 2019). More certification programs prefer to use juries rather than individual reviews, and most of these juries are composed of 2–5 experts, which is designed to ensure the objectivity of the evaluation. In addition to experts as jurors, some programs include students and candidates themselves as jurors. For example, in the certification program at the University of Freiburg, the experts enter the actual classroom to evaluate the teachers, and at the end of the class, the teachers and students receive a questionnaire to rate the teachers’ performance (Dubow and Gundermann, 2017). In the case of the O’Down evaluation, the students evaluate the teacher’s performance online. The multi-perspective rubric seems to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the teacher (O’Dowd, 2018). However, there are still two issues worth noting. First, in a jury that is generally dominated by language experts and less or no subject matter experts, can these language experts scientifically judge that the teachers’ organization of professional content in their teaching is reasonable? After all, EMI teaching is ultimately about the expertise that students are expected to learn through English. On the other hand, teachers’ own perspectives and those of their students are very informative, but certification, after all, needs to be scientific, and students’ evaluations are mostly based on their own experiences, which can be influenced by many other factors, so objectivity needs to be enhanced, which requires the designers of certification programs to rationalize the percentage of student ratings.

Unlike the results obtained from many standardized tests, the evaluator’s job in the program we describe is not just to score the test takers. Evaluators need to provide teachers with more explicit feedback on what the test takers are doing well and what they are missing. Upon completion of the TOEPAS assessment, each test taker receives a detailed feedback report that describes their language performance characteristics in five criteria: fluency, pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, and interaction. In addition to the written feedback, candidates will also receive a digital video recording of their performance. Notably, candidates are also invited to a follow-up meeting with one of the examiners, during which the examiner will provide further explanation of the teacher’s performance and give appropriate advice (Dimova, 2017). There are also programs that likewise provide teachers with suggestions for follow-up professional development to help them address current problems in their teaching (Gundermann and Dubow, 2018).

The perception of the certification

Several articles have also investigated faculty perceptions of accreditation. Combing through the relevant literature reveals that there is a fragmentation between faculty perceptions of EMI accreditation and their sentiments. On the one hand, offering EMI accreditation is necessary in the perceptions of most EMI faculty. Macaro and Han (2020) found, through a survey of 133 Chinese EMI faculty, that overall, the majority of respondents believed EMI accreditation was important at the personal, institutional, and international levels (Macaro and Han, 2020). The same authors’ study in 2021 found through a survey of seven countries that some respondents indicated that although their university did not offer accreditation, their perception of accreditation was positive or that they “preferred” to have a standard system (Macaro et al., 2020). However, when EMI faculty work in research universities where research performance is the core of assessment, EMI certification is not beneficial for career advancement and is seen as a means of pressuring faculty due to the time and effort required, which often exacerbates faculty tasks. In this context, many respondents showed negative reactions to EMI certification: about a quarter of professors felt that EMI certification was “not at all important” for themselves, their departments or universities, nationally or globally (Park et al., 2022). Similar results were found in Macaro’s survey, where even though an EMI certification system exists, some faculty members are not strongly motivated to become certified unless certification is part of the university’s assessment metrics or it facilitates faculty professional advancement (Macaro and Han, 2020). The above results seem to indicate that EMI teacher certification cannot exist in isolation. Certification needs to be integrated with teacher access systems, promotion systems and so on.

Conclusion and recommendation

After surveying 38 articles related to the professional competencies and certification programs for EMI teachers, the following conclusions and recommendations were drawn. The components of EMI teacher professionalism can include language proficiency, pedagogical competencies, intercultural competencies, and EMI awareness. Among these components, the most existing research on language competence has been conducted and discussed in detail from different perspectives on the language competencies that distinguish EMI teachers from general foreign language teachers, and many scholars have devised professional standards for language competencies. Many scholars have also conducted research on teaching competencies, and due to the shift in the language of instruction, most discussions of teaching competencies have combined teaching and English to form unique teaching competencies for EMI teachers. Intercultural competencies arise from the diverse student component of EMI classrooms, a competency that not only requires teachers to be able to communicate with students who come from different cultures but also teachers to help them overcome academic and cultural differences and quickly integrate into the local culture, among other things. Only a few studies that have explored the professionalization component have included EMI awareness, and there is still no consensus on what EMI teachers’ perceptions of EMI include and what standards they need to meet. The philosophy behind these professionalization components shows that professional development for teachers is seen as a learning experience through which teachers can perform better in the classroom and improve the quality of their teaching (Airey, 2015). The connotation of professional development guided by this philosophy lacks a focus on the development and professionalization of teachers as individuals. The content of teacher professionalism does not only require teachers to have the ability to improve the quality of their teaching, but they should also have the knowledge and ability to continuously develop themselves because the internal sustainability of teachers’ development is the key to their professional development (Mirzagitova and Akhmetov, 2015).

Overall, there are a relatively small number of certification programs designed specifically for EMI teachers. There are two different types of certification programs focusing on English language proficiency and teaching competency. The importance and validity of certification may be questioned in the absence of consensus on the content and standards of certification today. Galloway et al.’s study found that EMI teachers did not specifically envision the need for a credential to confirm their ability to teach through English-which students felt was necessary (Galloway et al., 2017). The only current certifications for EMI teachers are also district or school-based, and these certifications are not recognized across institutions, which results in professionals needing to retrain or reapply for certification, which limits mobility (Macaro et al., 2019; Macaro and Tian, 2020). Therefore, a growing number of researchers are calling for EMI certifications to be aligned with internationally recognized assessment standards (Dimova, 2017).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agarao-Fernandez, E., and Guzman, A. B. D. (2006). Exploring the dimensionality of teacher professionalization. Educ. Res. Policy Prac. 5, 211–224. doi: 10.1007/s10671-006-9010-x

Airey, J. (2015). “From stimulated recall to disciplinary literacy: summarizing ten years of research into teaching and learning in English” in English-medium instruction in European higher education. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 157–176.

Ball, P, and Lindsay, D. (2013). “Language Demands and Support for English-Medium Instruction in Tertiary Education: Learning from a Specific Context,” in English-Medium Instruction at Universities: Global Challenges. eds. D. Lasagabaster Doiz and J. Sierra (Multilingual Matters), 44–62.

Barnard, R. (2014). English medium instruction in Asian universities: some concerns and a suggested approach to dual-medium instruction. Indones J Appl Linguist 4, 10–22. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v4i1.597

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 3, 77–101.

Cambridge University Press and Assessment. (2023). Certificate in EMI skills (English as a medium of instruction). Available at: https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/teaching-english/teaching-qualifications/institutions/certificate-in-emi-skills/

Cañado, M. L. P. (2020). Addressing the research gap in teacher training for EMI: an evidence-based teacher education proposal in monolingual contexts. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 48:100927. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100927

Carrió-Pastor, M. L. (2020). “English as a Medium of Instruction: What About Pragmatic Competence?” in Internationalising learning in higher education: The challenges of English as a medium of instruction, 137–153.

Chen, Y., and Peng, J. (2019). Continuing professional development of EMI teachers: a Chinese case study. J. Educ. Teach. 45, 219–222. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2018.1548177

Costa, F., and Mair, O. (2022). Multimodality and Pronunciation in Iclhe (Integration of Content and Language in Higher Education) Training. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 16, 281–296.

Cots, J. M. (2013). “Introducing English-medium instruction at the University of Lleida, Spain: Intervention, beliefs and practices” in English-medium instruction at universities: Global challenges. UK, Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 106130.

Crespo, B., and Tojeiro, A. L. (2018). “Emi Teacher Training at the University of a Coruña” in Paper presented at the 4th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAD’18)

Dafouz, E., Núñez, B., Sancho, C., and Foran, D. (2007). Integrating CLIL at the tertiary level: teachers’ and students’ reactions. Diverse contexts converging goals. Content Lang Integr Learn Europe 4, 91–102.

Dang, T. K. A., and Vu, T. T. P. (2020). English-medium instruction in the Australian higher education: untold stories of academics from non-native English-speaking backgrounds. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 21, 279–300. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2019.1641350

Dearden, J. (2014). English as a medium of instruction-a growing global phenomenon. British Council. Available at: http://www.britishcouncil.org/education/ihe/knowledge-centre/english-language-higher-education/report-english-medium-instruction

Díaz Pérez, W., Ellison, M., Harumi, I., Kärkkäinen, K., Langé, G., Lee, J., et al. (2019). Implementing internationalization of academia: Teaching, Learning and Research through English.

Dimova, S. (2017). Life after Oral English certification: the consequences of the test of oral English proficiency for academic staff for EMI lecturers. Engl. Specif. Purp. 46, 45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2016.12.004

Dimova, S. (2020). Language assessment of EMI content teachers: what norms. Lang Percept Pract Multiling Universit, 351–378. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-38755-6_14

Dimova, S. (2021). Certifying lecturers’ English language skills for teaching in English-medium instruction programs in higher education. La certification des compétences langagières des enseignants pour dispenser des cours en anglais dans l’enseignement supérieur. ASp. 79, 29–47. doi: 10.4000/asp.7056

Dimova, S., and Kling, J. (2018). Assessing English-medium instruction lecturer language proficiency across disciplines. TESOL Q. 52, 634–656. doi: 10.1002/tesq.454

Dubow, G., and Gundermann, S. (2017). Certifying the linguistic and communicative competencies of teachers in English-medium instruction programmes. Lang Learn High Educ 7, 475–487. doi: 10.1515/cercles-2017-0021

Dubow, G., Gundermann, S., and Northover, L. (2021). “Establishing quality criteria and an EMI certification procedure” in Research methods in English medium instruction (Routledge), 75–91.

Fonseca, L. C., Corbett, J. B., and Costa, J. A. (2020). Enhancing academic literacies through EMI training: three perspectives on teaching towards the Certificatein EMI skills at the University of São Paulo. Letras, 195–226. doi: 10.5902/2176148548371

Fortanet-Gómez, I. (2020). “The dimensions of EMI in the international classroom: training teachers for the future university” in Teacher training for English-medium instruction in higher education (IGI Global), 1–20.

Galloway, N., Kriukow, J., and Numajiri, T. (2017). Internationalisation, higher education and the growing demand for English: an investigation into the English medium of instruction (EMI) movement in China and Japan. Available at: https://englishagenda.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/attachments/h035_eltra_internationalisation_he_and_the_growing_demand_for_english_a4_final_web.pdf

Gundermann, S., and Dubow, G. (2018). Ensuring quality in EMI: developing an assessment procedure at the University of Freiburg. Bull VALS-ASLA 107, 113–125.

Gustafsson, H. (2020). Capturing EMI teachers’ linguistic needs: a usage-based perspective. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 23, 1071–1082. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1425367

Helm, F., and Guarda, M. (2015). “Improvisation is not allowed in a second language”: a survey of italian lecturers’concerns about teaching their subjects through english. Lang. Learn. High. Educ. 5, 353–373.

Hendriks, B., and van Meurs, F. (2022). Dutch students’ evaluations of EMI and L1MOI lectures: the role of non-native pronunciation. System 108:102849. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2022.102849

Jiang, L., Zhang, L. J., and May, S. (2019). Implementing English-medium instruction (EMI) in China: teachers’ practices and perceptions, and students’ learning motivation and needs. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 22, 107–119. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2016.1231166

Klaassen, R. G., and Bos, M. (2010). English language screening for scientific staff at Delft University of Technology. HERMES-J Lang Commun Bus 45, 61–75. doi: 10.7146/hjlcb.v23i45.97347

Kling, J., and Hjulmand, L. L. (2008). “PLATE–project in language assessment for teaching in English” in Realizing content and language integration in higher education, 191–200.

Macaro, E., Akincioglu, M., and Han, S. (2020). English medium instruction in higher education: teacher perspectives on professional development and certification. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 30, 144–157. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12272

Macaro, E., and Han, S. (2020). English medium instruction in China’s higher education: teachers’ perspectives of competencies, certification and professional development. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 41, 219–231. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1611838

Macaro, E., Jiménez Muñoz, A., and Lasagabaster, D. (2019). The importance of certification of English medium instruction teachers in higher education in Spain.

Macaro, E., and Tian, L. (2020). Developing EMI teachers through a collaborative research model. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev., 1–16. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2020.1862131

Margić, B. D., and Vodopija-Krstanović, I. (2018). Language development for English-medium instruction: teachers’ perceptions, reflections and learning. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 35, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.06.005

Martínez, P. B., and González, D. (2017). Linguistic policy framework document for the internationalisation of the Spanish university system. In: CRUE-IC working subgroup on linguistic policy. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

Mirzagitova, A. L., and Akhmetov, L. G. (2015). Self-development of pedagogical competence of future teacher. Int. Educ. Stud. 8, 114–121. doi: 10.5539/ies.v8n3p114

Morell, T., Aleson-Carbonell, M., and Escabias-Lloret, P. (2022a). Prof-teaching: an English-medium instruction professional development program with a digital, linguistic and pedagogical approach. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 16, 392–411. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2022.2052298

Morell, T., Beltrán-Palanques, V., and Norte, N. (2022b). A multimodal analysis of pair work engagement episodes: implications for EMI lecturer training. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 58:101124. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101124

O’Dowd, R. (2018). The training and accreditation of teachers for English medium instruction: an overview of practice in European universities. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 21, 553–563. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1491945

Park, S., Kim, S.-Y., Lee, H., and Kim, E. G. (2022). Professional development for english-medium instruction professors at korean universities. System 109:102862.

Pilkinton-Pihko, D. (2013). English-medium instruction: Seeking assessment criteria for spoken professional English.

Piquer-Píriz, A. M., and Castellano-Risco, I. O. “Lecturers’ Training Needs in Emi Programmes: Beyond Language Competence.” (2021).

Richards, J. C., and Pun, J. (2022). Teacher strategies in implementing English medium instruction. ELT J. 76, 227–237. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccab081

Rubio-Alcalá, F. D., and Mallorquín, S. (2020). “Teacher training competences and subsequent training Design for Higher Education Plurilingual Programs” in Teacher training for English-medium instruction in higher education (IGI Global), 41–61.

Safipour, J., Wenneberg, S., and Hadziabdic, E. (2017). Experience of education in the international classroom--a systematic literature review. J. Int. Stud. 7, 806–824. doi: 10.32674/jis.v7i3.302

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 104, 333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Studer, P. (2015). Coping with English: students’ perceptions of their teachers’ linguistic competence in undergraduate science teaching. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 25, 183–201. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12062

Troia, M. (2013). On enhancing professional development within an internationalisation context. Unpublished PhD Dissertation. University of Groningen, Netherlands.

Tsui, C. (2017). EMI teacher development programs in Taiwan. English as a medium of instruction in higher education: implementations and classroom practices in Taiwan, 165–182.

Uehara, T., and Kojima, N. (2021). Prioritizing english-medium instruction teachers’ needs for faculty development and institutional support: a best–worst scaling approach. Educ. Sci. 11:384.

Ulla, M. B., Bucol, J. L., and Ayuthaya, P. D. N. (2022). English language curriculum reform strategies: the impact of EMI on students’ language proficiency. Ampersand 9:100101. doi: 10.1016/j.amper.2022.100101

Wang, C. (2023). Commanding the class in a foreign tongue: the influence of language proficiency and intercultural competence on classroom leadership. Educ. Urban Soc. 55, 34–55. doi: 10.1177/00131245211048428

Keywords: English medium instruction (EMI), professional development, professional competency, certification, teacher

Citation: Sun Y (2023) The professionalization of English medium instruction lecturer: content and certification. Front. Educ. 8:1191267. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1191267

Edited by:

Samantha Curle, University of Bath, United KingdomReviewed by:

Anne Li Jiang, Northeast Normal University, ChinaYi-Ping Huang, National Chengchi University, Taiwan

Copyright © 2023 Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Sun, sunyi2139@163.com

Yi Sun

Yi Sun